In 1967, Mel Brooks showed us that one of the best ways to combat evil ideas is with humor when he released “The Producers,” a satirical comedy that dismissed Nazis as subjects of mockery and laughter. The following year, a comedy group named Firesign Theater released their first album, Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Him. The first track on that album, titled Temporarily Humbolt County, is a 9 minute and 14 second humorous skewering of the historic displacement of native Americans. As an example, this is how they characterized the “good faith” treaty negotiations of the United States government:

RAIL PASSENGER: Are we in Goshen Yet?

CONDUCTOR: Can't go no further. This here's Injun Territory!

GOVERNMENT AGENT: Well, then! It's Treaty Time!

A brass band enters, playing "Hail to the Chief"

GOVERNMENT AGENT: My fellow Redskins! Speaking for the Great White Father in Washington and all the American People, let me say we respect you savages for your Native Ability to instantly Adapt and Survive in whatever Godforsaken wilderness we move you to. Out there. Sign here.

If you have a spare 42 minutes, you can listen to the entire album below.

But it’s another section of that routine that is particularly relevant to today’s post. It’s where they satirized decades of forced attendance at government boarding schools:

TOURIST: Howdy there, colorful replica of America's past! When is the exciting in its primitive splendor Snake Dance going to take place?

INDIAN: It's usually in August, but with all our children off in Indian School there's no one left to do the ceremonies.

Native child gets off the bus.

CHILD: Hiya, Pop! I'm home!

INDIAN: Hello, Soaring Eagle! It's good to have your back from school!

CHILD: Aw, come on! Call me Eddie! I'm an American now!

But the reality is that for over a century, native children sent to government schools were not returning as Americans, at least not in the sense that they enjoyed the rights and privileges of American citizenship. No native American did.

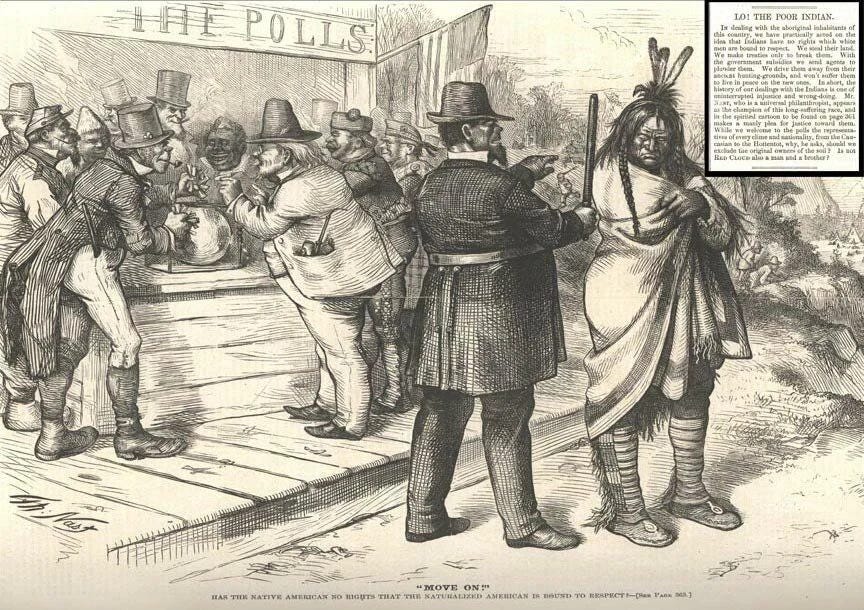

From the first days of the Republic, the legal and political status of native Americans had been ambiguous at best and often exclusionary. Whether or not citizenship applied to natives and to what degree was subject to constantly changing policies affecting native sovereignty and inclusion in the rights and privileges of the United States. In the 18th/19th century, tribes were treated as sovereign, autonomous nations … dealt with by treaties that reinforced the idea that native Americans were not citizens of the United States. These treaties were more often than not subject to political whims. An example is the 1868 treaty signed at Fort Laramie that recognized the Black Hills as exclusively belonging to the Sioux. That lasted until 1874 when gold was discovered in the Black Hills and the United States quickly reneged on the deal, redrawing the boundaries of the Sioux nation to exclude their possession of the gold-rich hills.

A major challenge to the exclusion of native Americans from United States citizenship was made in 1884 by John Elk of the Winnebago tribe. Born on a reservation, Elk had left his tribe to live and work in Omaha where he had been paying taxes. He then registered to vote in a city election, but the registrar, Charles Wilkins, denied him that right on the basis that he was an Indian and therefore was not an American citizen. Elk sued Wilkins, claiming that under the 14th and 15th amendments to the United States Constitution he was rightfully a citizen of the United States. He lost in the lower court, so Elk appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

In Elk v. Wilkins, the Supreme Court dealt with the issue of birthright citizenship. Elk had voluntarily given up his tribal affiliation, was living in an American city, spoke English, paid taxes, and … though born on a reservation … had been born within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. However, the Supreme Court ruled that neither treaty nor statute had ever naturalized Elk as an American citizen and the 14th amendment didn’t apply as Elk had been born subject to an Indian Nation that was considered an alien power.

That decision left native Americans in legal uncertainty for the next four decades. Some were able to obtain citizenship through military service, particularly in World War I when thousands of native Americans signed up to serve with no promise that citizenship would be granted (even greater numbers served in World War II). It wasn’t until late in 1919 that Congress passed H.R. 5007, granting citizenship to those that served. Earlier, in 1887, the Dawes act had granted citizenship to native Americans who accepted land allotments as part of forced assimilation. But this patchwork of citizenship grants always fell short of addressing the issue on a national level.

Today, June 2nd, 1924, the debate over native American citizenship was finally settled when the 20th President of the United States, Calvin Coolidge, signed the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. This act not only settled the citizenship question, but it also protected other rights that had been previously granted in the past

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.

While the act granted well-deserved citizenship to native Americans, it remains a stain that native Americans had to struggle through 30 Presidents to obtain a right that most Americans had been automatically granted. And, while a major victory, it did not end the struggle. Natives still had to fight for voting rights, as these were granted by the states. It would be more than another 4 decades before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 would grant all native Americans voting rights on the national level, and even then, it would require additional legislation to protect that right. It wasn’t until 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Indian Civil Rights Act, recognizing that native American’s were entitled to equal protection under the law, and were fully entitled to Constitutional protections and the Bill of Rights. Yet, even today, the original Americans often have to struggle to be recognized as fully Americans.

NEXT WEEK: When did the American Revolution begin?

...and the struggle is still not really over. Native American's don't actually own their own reservations. Reservation land is owned by the federal government who acts as stewards, setting the rules. If you want to understand that the economic theory of socialism simply doesn't work, you don't need to look back to the bad old days of the Soviet Union. You can stay right here at home and look at the native American reservation system.

My Indigenous family members through my brother's marriage to a woman from the Grovant tribe from MT, have strong feelings about all of these issues. They still struggle with discrimination, and profiling in northern MN. Thanks for writing this.