OK, Subscribers, set your way-back machines for 480 BC, at a pass named Thermopylae in ancient Greece. Yes, this is the brave stand of King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans against Xerxes I and his Persian army. It’s true that Leonidas only had about 300 Spartans, but what is often not mentioned is that he had about 7,000 other Greek soldiers defending the pass as well. Still, when you consider that the Spartans were in the front and facing a Persian army numbering in the hundreds of thousands, their stand was still remarkable. Xerxes knew that his overwhelmingly larger force would slaughter the Greeks (they did, but got a bloody nose doing it), so he called upon Leonidas to lay down his weapons. The King’s reply has gone down in history as some of the greatest words of defiance ever spoken … Molon Labe (Mow Lawn Lah Bay), which translates as “come and take them.”

And, as a subscriber, you’re likely wondering what this has to do with American history, but I told you that story to tell you this one about a small settlement in Mexican Texas and a cannon that sparked a revolution.

The whole thing started with the Mexican Constitution of 1824. Mexican Texas at the time was almost wholly unsettled land, that is if one doesn’t count the more than 50 indigenous people’s tribes who inhabited the area … which they didn’t. These tribes were in constant conflict with each other and had no problem with raiding and killing settlers. Mexico wanted to settle the area, but the Mexican people didn’t want to as it was considered too dangerous. So, in 1824 Mexico hatched a clever scheme. They would offer free land to American settlers (considered much less risk-avoidant) who agreed to live under the new Constitution. The only snag was that this invitation was chiefly attractive to America’s agricultural south where many potential immigrants owned slaves. The new Constitution had abolished slavery in Mexico, but they so earnestly wanted Americans to settle the area for them that Mexico exempted them from the Constitution’s slavery ban.

Now flash forward to 1835. You’re in a small Texian (U.S. immigrants) settlement in southeast Mexican Texas called Gonzales (roughly between present-day San Antonio and Houston). Since being founded it had suffered from repeated raids from multiple indigenous tribes, including one raid that destroyed the town and required it to be rebuilt. The Mexican authorities had no troops available to help defend the town, but they did loan the town a 6-pound cannon … reasonably useless against indigenous raids.

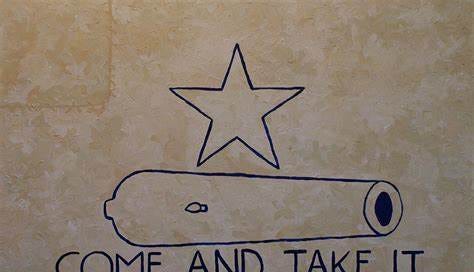

For many reasons … top of the list being Santa Anna trashing the Constitution of 1824 and declaring himself Dictator… tensions had been growing between the American settlers and their new government for some time now, and the Mexican authorities were reconsidering the wisdom of leaving artillery in the hands of potential rebels. They asked Gonzales to return the loaned cannon. Gonzales answered with the message “come and take it.” So, that’s exactly what the Mexicans did, sending a force of 100 Dragoons (mounted infantry) to retrieve the cannon. Gonzales was located on the other side of a river from the approach of the Dragoons. When they arrived at Gonzales, they looked across the river and saw the cannon, armed men in defensive positions, and a banner with a lone star, a cannon, and the words “come and take it” waving in the wind.

The Mexican commander decided to camp across the river and send a final request for the peaceful return of the cannon. On the Gonzales side, those armed men the Mexicans saw became known as the “Old Eighteen,” because that’s how many there were of them. They tried a stalling tactic, saying their commander was out of town and would be returning in a few days, but none of them were authorized to negotiate in his absence. The Mexicans then waited two days for the Texian commander’s “return,” while the Texians spent the time recruiting reinforcements. Today, October 2, 1835, the defenders of Gonzales now numbered 150 or more, and they were itchin’ for a fight. It was the Texians who crossed the river and attacked the Mexicans. They even got off one shot from the cannon before the Mexicans withdrew. The first battle of the Texas Revolution had been fought and won at Gonzales. Six months later, some of the defenders at Gonzales would once again face Santa Anna’s troops at a place called the Alamo.

Were the Gonzales defenders channeling the spirit of King Leonidas when they made their cry of defiance “come and take it?” Maybe, but it’s equally likely is that they were thinking of Colonel John McIntosh of the Continental Army during the American Revolution. While in command of Fort Morris in Georgia, a superior British force demanded the fort’s surrender. McIntosh, who knew his force would be overwhelmed in battle, nevertheless went all Leonidas on the British and replied, “As to surrendering the fort, receive this laconic reply: COME AND TAKE IT!". The British commander thought that to be so brazen that the Americans must have a much larger force than he knew defending the fort. Deciding that discretion was the better part of valor, the British retreated without attacking.

So perhaps Gonzales was inspired by Fort Morris, and Fort Morris was inspired by Thermopylae. Later, during the Civil War, Gonzales may have inspired Union Colonel Clark Weaver to respond to a Confederate demand for his surrender with, "In my opinion I can hold this post. If you want it, come and take it."

NEXT WEEK: Peanuts, Cracker Jacks, and Payoffs.

Great article. Liked the way you connected ancient and modern along same theme.